Home

25+ Years Under Ohio

More than a quarter of a century ago, Lou Plank and his wife, Lee, made up their minds to build an underground house. The only problem was, neither of them had any experience with structural design or construction.

"My education was in music," Plank says. "A year and a half of research was my 'massive' background."

When Plank says "research," he means the basic, from-scratch kind. "Back in the '70s, there was not a lot of information available," he recalls. "I had only one thesis on underground architecture to assist me."

"My education was in music," Plank says. "A year and a half of research was my 'massive' background."

When Plank says "research," he means the basic, from-scratch kind. "Back in the '70s, there was not a lot of information available," he recalls. "I had only one thesis on underground architecture to assist me."

But, why?

In the mid-1970s, the United States suffered what was commonly known as the original "energy crisis." Many oil-exporting countries, upset with American foreign policy, imposed an embargo that significantly reduced US petroleum imports. Automobile drivers frequently found service stations closed for lack of gasoline; at open stations drivers had to wait in long lines to fill up their cars. As energy supplies tightened, the cost of heating buildings rose, too. In 1979, President Jimmy Carter instituted mandatory temperature restrictions on nonresidential buildings and urged individuals to adopt similar guidelines, suggesting they wear sweaters to keep warm. By then, the Planks had already decided to save energy by building their home underground.

They had other reasons, too. "My goal was to beat the costs of above-ground construction," Plank says. With the help of a friend, the couple did much of the construction and finishing work themselves, saving nearly half the cost of a conventional house.

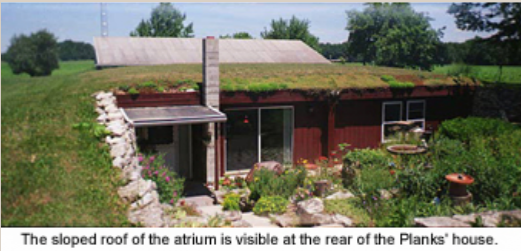

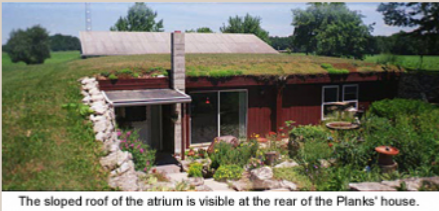

Their third motivation was to reduce maintenance efforts by protecting all sides of their home with soil. After living in the home for a quarter of a century, Plank is obviously pleased with the result: "I still like the low maintenance," he says. "No roof repairs; we do mow our roof once a week, however!"

OK, Then, How?

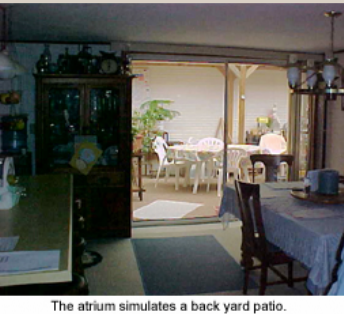

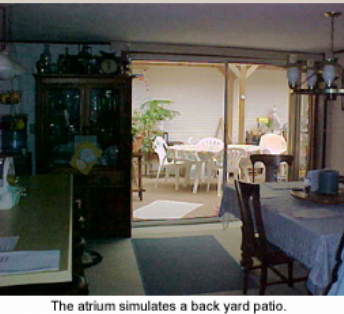

The Planks' first task was designing the home. One of their main concerns was get enough natural light into the house, and they approached the problem on two fronts. Creating a sunken courtyard on the south side of the building exposed part of one wall. In addition to the front door and a couple of windows, an 8-foot patio door on this wall of the living room admits daylight and also facilitates moving furniture in and out of the house. To allow natural light to enter the house from another direction, Plank placed an 800-square-foot atrium along the north side of the house. Sunshine pours through the clear fiberglass roof of the atrium, bounces off the north wall, and reflects into the house through windows. Another 8-foot-wide sliding glass door opens onto the atrium, which serves as an "outdoor" patio, adding both physical and psychological space to the 2,200-square-foot home.

In the mid-1970s, the United States suffered what was commonly known as the original "energy crisis." Many oil-exporting countries, upset with American foreign policy, imposed an embargo that significantly reduced US petroleum imports. Automobile drivers frequently found service stations closed for lack of gasoline; at open stations drivers had to wait in long lines to fill up their cars. As energy supplies tightened, the cost of heating buildings rose, too. In 1979, President Jimmy Carter instituted mandatory temperature restrictions on nonresidential buildings and urged individuals to adopt similar guidelines, suggesting they wear sweaters to keep warm. By then, the Planks had already decided to save energy by building their home underground.

They had other reasons, too. "My goal was to beat the costs of above-ground construction," Plank says. With the help of a friend, the couple did much of the construction and finishing work themselves, saving nearly half the cost of a conventional house.

Their third motivation was to reduce maintenance efforts by protecting all sides of their home with soil. After living in the home for a quarter of a century, Plank is obviously pleased with the result: "I still like the low maintenance," he says. "No roof repairs; we do mow our roof once a week, however!"

OK, Then, How?

The Planks' first task was designing the home. One of their main concerns was get enough natural light into the house, and they approached the problem on two fronts. Creating a sunken courtyard on the south side of the building exposed part of one wall. In addition to the front door and a couple of windows, an 8-foot patio door on this wall of the living room admits daylight and also facilitates moving furniture in and out of the house. To allow natural light to enter the house from another direction, Plank placed an 800-square-foot atrium along the north side of the house. Sunshine pours through the clear fiberglass roof of the atrium, bounces off the north wall, and reflects into the house through windows. Another 8-foot-wide sliding glass door opens onto the atrium, which serves as an "outdoor" patio, adding both physical and psychological space to the 2,200-square-foot home.

More than a quarter of a century ago, Lou Plank and his wife, Lee, made up their minds to build an underground house. The only problem was, neither of them had any experience with structural design or construction.

"My education was in music," Plank says. "A year and a half of research was my 'massive' background."

When Plank says "research," he means the basic, from-scratch kind. "Back in the '70s, there was not a lot of information available," he recalls. "I had only one thesis on underground architecture to assist me."

"My education was in music," Plank says. "A year and a half of research was my 'massive' background."

When Plank says "research," he means the basic, from-scratch kind. "Back in the '70s, there was not a lot of information available," he recalls. "I had only one thesis on underground architecture to assist me."

Unless otherwise attributed, all content is © Loretta Hall, 2000-2024.

But, why?

In the mid-1970s, the United States suffered what was commonly known as the original "energy crisis." Many oil-exporting countries, upset with American foreign policy, imposed an embargo that significantly reduced US petroleum imports. Automobile drivers frequently found service stations closed for lack of gasoline; at open stations drivers had to wait in long lines to fill up their cars. As energy supplies tightened, the cost of heating buildings rose, too. In 1979, President Jimmy Carter instituted mandatory temperature restrictions on nonresidential buildings and urged individuals to adopt similar guidelines, suggesting they wear sweaters to keep warm. By then, the Planks had already decided to save energy by building their home underground.

They had other reasons, too. "My goal was to beat the costs of above-ground construction," Plank says. With the help of a friend, the couple did much of the construction and finishing work themselves, saving nearly half the cost of a conventional house.

Their third motivation was to reduce maintenance efforts by protecting all sides of their home with soil. After living in the home for a quarter of a century, Plank is obviously pleased with the result: "I still like the low maintenance," he says. "No roof repairs; we do mow our roof once a week, however!"

OK, Then, How?

The Planks' first task was designing the home. One of their main concerns was get enough natural light into the house, and they approached the problem on two fronts. Creating a sunken courtyard on the south side of the building exposed part of one wall. In addition to the front door and a couple of windows, an 8-foot patio door on this wall of the living room admits daylight and also facilitates moving furniture in and out of the house. To allow natural light to enter the house from another direction, Plank placed an 800-square-foot atrium along the north side of the house. Sunshine pours through the clear fiberglass roof of the atrium, bounces off the north wall, and reflects into the house through windows. Another 8-foot-wide sliding glass door opens onto the atrium, which serves as an "outdoor" patio, adding both physical and psychological space to the 2,200-square-foot home.

In the mid-1970s, the United States suffered what was commonly known as the original "energy crisis." Many oil-exporting countries, upset with American foreign policy, imposed an embargo that significantly reduced US petroleum imports. Automobile drivers frequently found service stations closed for lack of gasoline; at open stations drivers had to wait in long lines to fill up their cars. As energy supplies tightened, the cost of heating buildings rose, too. In 1979, President Jimmy Carter instituted mandatory temperature restrictions on nonresidential buildings and urged individuals to adopt similar guidelines, suggesting they wear sweaters to keep warm. By then, the Planks had already decided to save energy by building their home underground.

They had other reasons, too. "My goal was to beat the costs of above-ground construction," Plank says. With the help of a friend, the couple did much of the construction and finishing work themselves, saving nearly half the cost of a conventional house.

Their third motivation was to reduce maintenance efforts by protecting all sides of their home with soil. After living in the home for a quarter of a century, Plank is obviously pleased with the result: "I still like the low maintenance," he says. "No roof repairs; we do mow our roof once a week, however!"

OK, Then, How?

The Planks' first task was designing the home. One of their main concerns was get enough natural light into the house, and they approached the problem on two fronts. Creating a sunken courtyard on the south side of the building exposed part of one wall. In addition to the front door and a couple of windows, an 8-foot patio door on this wall of the living room admits daylight and also facilitates moving furniture in and out of the house. To allow natural light to enter the house from another direction, Plank placed an 800-square-foot atrium along the north side of the house. Sunshine pours through the clear fiberglass roof of the atrium, bounces off the north wall, and reflects into the house through windows. Another 8-foot-wide sliding glass door opens onto the atrium, which serves as an "outdoor" patio, adding both physical and psychological space to the 2,200-square-foot home.

Plank even designed the house to allow the possibility of expansion. A doorway framed into the concrete kitchen wall serves as a shallow "can pantry." If an extra room or an attached garage were to be added to the home, the doorway could easily be opened to connect the addition to the existing house.

Designing the house took research and creativity, and so did the actual construction. For openers, Plank learned that, other than the terraced front yard, the excavation would have to be dug with vertical surfaces to provide stable support for the house's walls. Rather than burying water pipes and electrical wiring in the concrete floor, Plank installed them behind plasterboard walls spaced out from the house's 8-inch-thick concrete shell with 2-inch-by-2-inch boards. Plasterboard ceilings in some rooms serve a similar purpose.

One of the biggest challenges was building an economical, efficient roof that could support a load of 195 pounds per square foot. Plank decided on a hollow-core prestressed concrete plank system known as Flexicore. The precast planks were trucked to the site, lifted into place, secured to the walls and each other, and then covered with a 5-inch-thick pour of reinforced concrete. The integrated system held secure for twenty years before a small leak appeared. "I took off the dirt to see what was causing the leak," Plank says. "The asphalt-based seal that I used was about gone-it just disappeared. The concrete had cracked in a couple of places due to shrinkage." After sealing the small cracks, he covered the roof with a new coat of asphalt-based sealant and replaced the housetop lawn.

The Bottom Line

Lou and Lee Plank moved into their not-quite-finished underground house in November 1978 as winter set in. Since then, thousands of people have seen their home, either individually or on organized tours. "Most people say when they walk in for the first time that it is 'not at all what I expected-this is really nice,'" Plank reports. "Most people will remark on the amount of natural light that is in the house."

As for the residents themselves, the house has been more than satisfactory. "The best part of living underground (besides energy savings and low maintenance) is the quiet and peaceful background," Plank says. "When storms arrive, we literally don't know it." There are some minor limitations, however. "The least liked part of living underground is the short-range view," he continues. "Lee says she misses looking out a window when doing the dishes."

Overall, however, the Planks are pleased with their experience and eager to share information with others. If you would like to ask them a question, just submit it through the SubsurfaceBuildings "Contact Us" page. And if you schedule an appointment in advance, they are even willing to show you around their northwestern Ohio home.

"We've been here so long that it's not unusual for us anymore," Plank says. "It's just home!"

Designing the house took research and creativity, and so did the actual construction. For openers, Plank learned that, other than the terraced front yard, the excavation would have to be dug with vertical surfaces to provide stable support for the house's walls. Rather than burying water pipes and electrical wiring in the concrete floor, Plank installed them behind plasterboard walls spaced out from the house's 8-inch-thick concrete shell with 2-inch-by-2-inch boards. Plasterboard ceilings in some rooms serve a similar purpose.

One of the biggest challenges was building an economical, efficient roof that could support a load of 195 pounds per square foot. Plank decided on a hollow-core prestressed concrete plank system known as Flexicore. The precast planks were trucked to the site, lifted into place, secured to the walls and each other, and then covered with a 5-inch-thick pour of reinforced concrete. The integrated system held secure for twenty years before a small leak appeared. "I took off the dirt to see what was causing the leak," Plank says. "The asphalt-based seal that I used was about gone-it just disappeared. The concrete had cracked in a couple of places due to shrinkage." After sealing the small cracks, he covered the roof with a new coat of asphalt-based sealant and replaced the housetop lawn.

The Bottom Line

Lou and Lee Plank moved into their not-quite-finished underground house in November 1978 as winter set in. Since then, thousands of people have seen their home, either individually or on organized tours. "Most people say when they walk in for the first time that it is 'not at all what I expected-this is really nice,'" Plank reports. "Most people will remark on the amount of natural light that is in the house."

As for the residents themselves, the house has been more than satisfactory. "The best part of living underground (besides energy savings and low maintenance) is the quiet and peaceful background," Plank says. "When storms arrive, we literally don't know it." There are some minor limitations, however. "The least liked part of living underground is the short-range view," he continues. "Lee says she misses looking out a window when doing the dishes."

Overall, however, the Planks are pleased with their experience and eager to share information with others. If you would like to ask them a question, just submit it through the SubsurfaceBuildings "Contact Us" page. And if you schedule an appointment in advance, they are even willing to show you around their northwestern Ohio home.

"We've been here so long that it's not unusual for us anymore," Plank says. "It's just home!"

Lou and Lee Plank provided the information and photographs for this article. We thank them and wish them a "Happy Underversary"!

Unless otherwise attributed, all SubsurfaceBuildings.com content is © Loretta Hall, 2000-2024.

Plank even designed the house to allow the possibility of expansion. A doorway framed into the concrete kitchen wall serves as a shallow "can pantry." If an extra room or an attached garage were to be added to the home, the doorway could easily be opened to connect the addition to the existing house.

Designing the house took research and creativity, and so did the actual construction. For openers, Plank learned that, other than the terraced front yard, the excavation would have to be dug with vertical surfaces to provide stable support for the house's walls. Rather than burying water pipes and electrical wiring in the concrete floor, Plank installed them behind plasterboard walls spaced out from the house's 8-inch-thick concrete shell with 2-inch-by-2-inch boards. Plasterboard ceilings in some rooms serve a similar purpose.

One of the biggest challenges was building an economical, efficient roof that could support a load of 195 pounds per square foot. Plank decided on a hollow-core prestressed concrete plank system known as Flexicore. The precast planks were trucked to the site, lifted into place, secured to the walls and each other, and then covered with a 5-inch-thick pour of reinforced concrete. The integrated system held secure for twenty years before a small leak appeared. "I took off the dirt to see what was causing the leak," Plank says. "The asphalt-based seal that I used was about gone-it just disappeared. The concrete had cracked in a couple of places due to shrinkage." After sealing the small cracks, he covered the roof with a new coat of asphalt-based sealant and replaced the housetop lawn.

The Bottom Line

Lou and Lee Plank moved into their not-quite-finished underground house in November 1978 as winter set in. Since then, thousands of people have seen their home, either individually or on organized tours. "Most people say when they walk in for the first time that it is 'not at all what I expected-this is really nice,'" Plank reports. "Most people will remark on the amount of natural light that is in the house."

As for the residents themselves, the house has been more than satisfactory. "The best part of living underground (besides energy savings and low maintenance) is the quiet and peaceful background," Plank says. "When storms arrive, we literally don't know it." There are some minor limitations, however. "The least liked part of living underground is the short-range view," he continues. "Lee says she misses looking out a window when doing the dishes."

Overall, however, the Planks are pleased with their experience and eager to share information with others. If you would like to ask them a question, just submit it through the SubsurfaceBuildings "Contact Us" page. And if you schedule an appointment in advance, they are even willing to show you around their northwestern Ohio home.

"We've been here so long that it's not unusual for us anymore," Plank says. "It's just home!"

Designing the house took research and creativity, and so did the actual construction. For openers, Plank learned that, other than the terraced front yard, the excavation would have to be dug with vertical surfaces to provide stable support for the house's walls. Rather than burying water pipes and electrical wiring in the concrete floor, Plank installed them behind plasterboard walls spaced out from the house's 8-inch-thick concrete shell with 2-inch-by-2-inch boards. Plasterboard ceilings in some rooms serve a similar purpose.

One of the biggest challenges was building an economical, efficient roof that could support a load of 195 pounds per square foot. Plank decided on a hollow-core prestressed concrete plank system known as Flexicore. The precast planks were trucked to the site, lifted into place, secured to the walls and each other, and then covered with a 5-inch-thick pour of reinforced concrete. The integrated system held secure for twenty years before a small leak appeared. "I took off the dirt to see what was causing the leak," Plank says. "The asphalt-based seal that I used was about gone-it just disappeared. The concrete had cracked in a couple of places due to shrinkage." After sealing the small cracks, he covered the roof with a new coat of asphalt-based sealant and replaced the housetop lawn.

The Bottom Line

Lou and Lee Plank moved into their not-quite-finished underground house in November 1978 as winter set in. Since then, thousands of people have seen their home, either individually or on organized tours. "Most people say when they walk in for the first time that it is 'not at all what I expected-this is really nice,'" Plank reports. "Most people will remark on the amount of natural light that is in the house."

As for the residents themselves, the house has been more than satisfactory. "The best part of living underground (besides energy savings and low maintenance) is the quiet and peaceful background," Plank says. "When storms arrive, we literally don't know it." There are some minor limitations, however. "The least liked part of living underground is the short-range view," he continues. "Lee says she misses looking out a window when doing the dishes."

Overall, however, the Planks are pleased with their experience and eager to share information with others. If you would like to ask them a question, just submit it through the SubsurfaceBuildings "Contact Us" page. And if you schedule an appointment in advance, they are even willing to show you around their northwestern Ohio home.

"We've been here so long that it's not unusual for us anymore," Plank says. "It's just home!"

Lou and Lee Plank provided the information and photographs for this article.