Following his conversion experience, Wells began promoting underground architecture by writing magazine articles, self-publishing books, and lecturing at architecture schools.

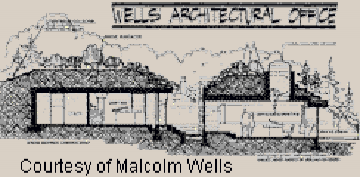

Cherry Hill Office (1971)

"In the early 1970s, realizing it was time to put up or shut up, I decided to build an [underground] architectural office for myself.... That's when the surprises began. The first one was that the open courtyard was actually quiet in spite of the truck traffic only 20 feet away. Another was the absolute silence of the innermost rooms."

"To cover the roof, rather than bring in topsoil from another site, I decided to see if topsoil could, in effect, be created. Once the brick and concrete structure had been waterproofed ... it was backfilled and covered with the lifeless subsoil we'd stockpiled when the site was excavated. Then, from a nearby town dump, we brought tons of leaves collected from the streets of that town and spread them there. The next spring, a miracle occurred: The site burst into life with every imaginable kind of weed and wildflower. It was an instant green area-without poisons, fertilizers, or topsoil. Within just a few years, I had a jungle on my hands.... At times, the birdsong seemed louder than the truck traffic. Maybe it was the site's way of expressing gratitude for having been spared the fate of every other site in the area; other sites, if they weren't asphalted to death, were kept in a perpetual stupor with poisons and mowing."

[In the photo at the top of this page, one corner of the roof of Wells' office building is barely visible through the empty trellis (at the back of the second rectangle from the bottom).]

Underground America Day

Wells' creativity and sense of humor are as fully developed as his understanding of earth-covered building design. His efforts to popularize underground architecture are often innovative. Every year he celebrates Underground America Day.

"On May 14th each year hundreds of millions of people all across this great land will do absolutely nothing about the national holiday I declared in 1974, and that's the way it should be. It's a holiday free of holiday obligations.... But if you're the partying type, here are some of the ways in which you can observe the big day: Dig a hole and put your house in it. Cover it up.... Touch a basement wall.... Draw a set of plans for an above-ground building-but don't build it."

Solaria

In the mid-1970s, near Philadelphia, Wells built the first version of one of his most famous residential designs. The long, narrow house's 16-foot-high south-facing wall consisted of solar collector panels above a wall of windows. The roof was covered with 2 feet of soil. The north wall was mostly buried, except for a short strip below the roof where windows alternated with massive support beams.

"All through the winter . . . we waited for word from the [house's owners]. January. February. March. . . . Finally Bob visited us and we all said, 'Well?' 'We didn't use the auxiliary heat at all.' So we had our first real proof, that under record conditions, solar heat and earth cover is a powerful combination, even in the northeastern part of the United States."

"This house is based on a design theme so simple, we've done dozens of variations on it and dozens more are possible."

Cape Cod House/Office (1980)

For passive solar-heating benefits, many earth-sheltered houses are designed with large window walls along an exposed south-facing wall. In 1980, Wells showed this concern does not have to be a constraint.

"When you have a stunning pond and forest view to the east you build facing east and find some other way to admit solar radiation."

The 110-foot-long house and office structure he built on Cape Cod was topped with a triple-glazed glass skylight that could be shielded with canvas shades to limit summer heat.

Underground Art Gallery

"The Underground Art Gallery on Cape Cod in which I have my office, built in 1988, is now almost totally hidden in the summertime by the lush growth on and around it. But when the leaves fall, its sixty-foot-long wall of glass admits warming sunlight. I'm writing this just inside a wall of insulating glass. The room is so bright I've had to draw the blinds a bit. Overhead, 100 tons of earth can no doubt feel the urgings of springtime in the roots. . . . Inside, the silence is so complete the loudest noise is the gliding of my pen across the paper. . . . I didn't plant the wild garden on the roof. The seeds arrived by breeze and bird and planted themselves in gratitude for my having added, not subtracted, land area when I built. . . . I'm underground, just where we all should be. Here, much of the rain that falls on the roof stays up there for days, percolating down through the deep humus and soil layers until it reaches the waterproofing, at which point it seeps out to the edge of the roof and drips into the surrounding soil. . . . Before the building was built the site was all barren subsoil, lifeless. Now it's a junior forest growing healthier by the year."

Looking Ahead from Below

"The resistance to underground architecture is due not only to inertia and unfamiliarity with earth-type building techniques but to fear of ridicule and fear of failure as well."

"Underground architecture is bound to succeed eventually. It has the most powerful of all possible allies: the living world. Rather than standing above Mother Earth, underground architecture lies in her arms."

Sources:

MalcolmWells.com

An Architect's Sketchbook of Underground Buildings, 1990.

Earth Sheltered Homes by Ahrens, Ellison, & Sterling, 1981.

"Nowhere to Go But Down," Progressive Architecture, 1965.

Recovering America: A More Gentle Way to Build, 1999.

"Underground! A More Gentle Way to Build," Designer/Builder, April 2000.

Underground Designs, 1977.

Cherry Hill Office (1971)

"In the early 1970s, realizing it was time to put up or shut up, I decided to build an [underground] architectural office for myself.... That's when the surprises began. The first one was that the open courtyard was actually quiet in spite of the truck traffic only 20 feet away. Another was the absolute silence of the innermost rooms."

"To cover the roof, rather than bring in topsoil from another site, I decided to see if topsoil could, in effect, be created. Once the brick and concrete structure had been waterproofed ... it was backfilled and covered with the lifeless subsoil we'd stockpiled when the site was excavated. Then, from a nearby town dump, we brought tons of leaves collected from the streets of that town and spread them there. The next spring, a miracle occurred: The site burst into life with every imaginable kind of weed and wildflower. It was an instant green area-without poisons, fertilizers, or topsoil. Within just a few years, I had a jungle on my hands.... At times, the birdsong seemed louder than the truck traffic. Maybe it was the site's way of expressing gratitude for having been spared the fate of every other site in the area; other sites, if they weren't asphalted to death, were kept in a perpetual stupor with poisons and mowing."

[In the photo at the top of this page, one corner of the roof of Wells' office building is barely visible through the empty trellis (at the back of the second rectangle from the bottom).]

Underground America Day

Wells' creativity and sense of humor are as fully developed as his understanding of earth-covered building design. His efforts to popularize underground architecture are often innovative. Every year he celebrates Underground America Day.

"On May 14th each year hundreds of millions of people all across this great land will do absolutely nothing about the national holiday I declared in 1974, and that's the way it should be. It's a holiday free of holiday obligations.... But if you're the partying type, here are some of the ways in which you can observe the big day: Dig a hole and put your house in it. Cover it up.... Touch a basement wall.... Draw a set of plans for an above-ground building-but don't build it."

Solaria

In the mid-1970s, near Philadelphia, Wells built the first version of one of his most famous residential designs. The long, narrow house's 16-foot-high south-facing wall consisted of solar collector panels above a wall of windows. The roof was covered with 2 feet of soil. The north wall was mostly buried, except for a short strip below the roof where windows alternated with massive support beams.

"All through the winter . . . we waited for word from the [house's owners]. January. February. March. . . . Finally Bob visited us and we all said, 'Well?' 'We didn't use the auxiliary heat at all.' So we had our first real proof, that under record conditions, solar heat and earth cover is a powerful combination, even in the northeastern part of the United States."

"This house is based on a design theme so simple, we've done dozens of variations on it and dozens more are possible."

Cape Cod House/Office (1980)

For passive solar-heating benefits, many earth-sheltered houses are designed with large window walls along an exposed south-facing wall. In 1980, Wells showed this concern does not have to be a constraint.

"When you have a stunning pond and forest view to the east you build facing east and find some other way to admit solar radiation."

The 110-foot-long house and office structure he built on Cape Cod was topped with a triple-glazed glass skylight that could be shielded with canvas shades to limit summer heat.

Underground Art Gallery

"The Underground Art Gallery on Cape Cod in which I have my office, built in 1988, is now almost totally hidden in the summertime by the lush growth on and around it. But when the leaves fall, its sixty-foot-long wall of glass admits warming sunlight. I'm writing this just inside a wall of insulating glass. The room is so bright I've had to draw the blinds a bit. Overhead, 100 tons of earth can no doubt feel the urgings of springtime in the roots. . . . Inside, the silence is so complete the loudest noise is the gliding of my pen across the paper. . . . I didn't plant the wild garden on the roof. The seeds arrived by breeze and bird and planted themselves in gratitude for my having added, not subtracted, land area when I built. . . . I'm underground, just where we all should be. Here, much of the rain that falls on the roof stays up there for days, percolating down through the deep humus and soil layers until it reaches the waterproofing, at which point it seeps out to the edge of the roof and drips into the surrounding soil. . . . Before the building was built the site was all barren subsoil, lifeless. Now it's a junior forest growing healthier by the year."

Looking Ahead from Below

"The resistance to underground architecture is due not only to inertia and unfamiliarity with earth-type building techniques but to fear of ridicule and fear of failure as well."

"Underground architecture is bound to succeed eventually. It has the most powerful of all possible allies: the living world. Rather than standing above Mother Earth, underground architecture lies in her arms."

Sources:

MalcolmWells.com

An Architect's Sketchbook of Underground Buildings, 1990.

Earth Sheltered Homes by Ahrens, Ellison, & Sterling, 1981.

"Nowhere to Go But Down," Progressive Architecture, 1965.

Recovering America: A More Gentle Way to Build, 1999.

"Underground! A More Gentle Way to Build," Designer/Builder, April 2000.

Underground Designs, 1977.

Home

Architect of the Invisible

"When we can say honestly and without arrogance that [our works] are as beautiful and appropriate as the humblest work of Nature, then we'll be building--and living--as we should."

The words of architect Malcolm Wells are as striking as his building designs. For that reason, this article will consist largely of quotations in which Wells tells his own story.

"When we can say honestly and without arrogance that [our works] are as beautiful and appropriate as the humblest work of Nature, then we'll be building--and living--as we should."

The words of architect Malcolm Wells are as striking as his building designs. For that reason, this article will consist largely of quotations in which Wells tells his own story.

The words of architect Malcolm Wells are as striking as his building designs. For that reason, this article will consist largely of quotations in which Wells tells his own story.

Malcolm Wells passed away November 27, 2009. His contributions to ecologically sensitive architecture will endure.

"In 1959, at Taliesin West [near Phoenix, Arizona], I stepped out of the hot desert sunlight into this little open-to-the-air theatre, and marveled for a moment or two at Mr. [Frank Lloyd] Wright's genius, his ability to carry a design through into the tiniest of details, before it struck me that I was suddenly cool and comfortable there under a mantle of earth. It took me only five more years to get the message. In 1964, I suddenly had a brilliant and original idea: buildings should be underground!"

Wells says the environmental consciousness of the 1960s led him to the underground solution. He decided that "the goal of a truly appropriate architecture" should be "invisibility."

"The rules of life never change:

1. People can't draw energy directly from sunlight.

2. Plants can.

3. Plants can't live underground.

4. We can.

It's as simple as that."

Following his conversion experience, Wells began promoting underground architecture by writing magazine articles, self-publishing books, and lecturing at architecture schools.

Wells says the environmental consciousness of the 1960s led him to the underground solution. He decided that "the goal of a truly appropriate architecture" should be "invisibility."

"The rules of life never change:

1. People can't draw energy directly from sunlight.

2. Plants can.

3. Plants can't live underground.

4. We can.

It's as simple as that."

Following his conversion experience, Wells began promoting underground architecture by writing magazine articles, self-publishing books, and lecturing at architecture schools.

"In 1959, at Taliesin West [near Phoenix, Arizona], I stepped out of the hot desert sunlight into this little open-to-the-air theatre, and marveled for a moment or two at Mr. [Frank Lloyd] Wright's genius, his ability to carry a design through into the tiniest of details, before it struck me that I was suddenly cool and comfortable there under a mantle of earth. It took me only five more years to get the message. In 1964, I suddenly had a brilliant and original idea: buildings should be underground!"

Wells says the environmental consciousness of the 1960s led him to the underground solution. He decided that "the goal of a truly appropriate architecture" should be "invisibility."

"The rules of life never change:

1. People can't draw energy directly from sunlight.

2. Plants can.

3. Plants can't live underground.

4. We can.

It's as simple as that."

Wells says the environmental consciousness of the 1960s led him to the underground solution. He decided that "the goal of a truly appropriate architecture" should be "invisibility."

"The rules of life never change:

1. People can't draw energy directly from sunlight.

2. Plants can.

3. Plants can't live underground.

4. We can.

It's as simple as that."

Cherry Hill Office (1971)

"In the early 1970s, realizing it was time to put up or shut up, I decided to build an [underground] architectural office for myself.... That's when the surprises began. The first one was that the open courtyard was actually quiet in spite of the truck traffic only 20 feet away. Another was the absolute silence of the innermost rooms."

"To cover the roof, rather than bring in topsoil from another site, I decided to see if topsoil could, in effect, be created. Once the brick and concrete structure had been waterproofed ... it was backfilled and covered with the lifeless subsoil we'd stockpiled when the site was excavated. Then, from a nearby town dump, we brought tons of leaves collected from the streets of that town and spread them there. The next spring, a miracle occurred: The site burst into life with every imaginable kind of weed and wildflower. It was an instant green area-without poisons, fertilizers, or topsoil. Within just a few years, I had a jungle on my hands.... At times, the birdsong seemed louder than the truck traffic. Maybe it was the site's way of expressing gratitude for having been spared the fate of every other site in the area; other sites, if they weren't asphalted to death, were kept in a perpetual stupor with poisons and mowing."

[In the photo at the top of this page, one corner of the roof of Wells' office building is barely visible through the empty trellis (at the back of the second rectangle from the bottom).]

Underground America Day

Wells' creativity and sense of humor are as fully developed as his understanding of earth-covered building design. His efforts to popularize underground architecture are often innovative. Every year he celebrates Underground America Day.

"On May 14th each year hundreds of millions of people all across this great land will do absolutely nothing about the national holiday I declared in 1974, and that's the way it should be. It's a holiday free of holiday obligations.... But if you're the partying type, here are some of the ways in which you can observe the big day: Dig a hole and put your house in it. Cover it up.... Touch a basement wall.... Draw a set of plans for an above-ground building-but don't build it."

Solaria

In the mid-1970s, near Philadelphia, Wells built the first version of one of his most famous residential designs. The long, narrow house's 16-foot-high south-facing wall consisted of solar collector panels above a wall of windows. The roof was covered with 2 feet of soil. The north wall was mostly buried, except for a short strip below the roof where windows alternated with massive support beams.

"All through the winter . . . we waited for word from the [house's owners]. January. February. March. . . . Finally Bob visited us and we all said, 'Well?' 'We didn't use the auxiliary heat at all.' So we had our first real proof, that under record conditions, solar heat and earth cover is a powerful combination, even in the northeastern part of the United States."

"This house is based on a design theme so simple, we've done dozens of variations on it and dozens more are possible."

Cape Cod House/Office (1980)

For passive solar-heating benefits, many earth-sheltered houses are designed with large window walls along an exposed south-facing wall. In 1980, Wells showed this concern does not have to be a constraint.

"When you have a stunning pond and forest view to the east you build facing east and find some other way to admit solar radiation."

The 110-foot-long house and office structure he built on Cape Cod was topped with a triple-glazed glass skylight that could be shielded with canvas shades to limit summer heat.

Underground Art Gallery

"The Underground Art Gallery on Cape Cod in which I have my office, built in 1988, is now almost totally hidden in the summertime by the lush growth on and around it. But when the leaves fall, its sixty-foot-long wall of glass admits warming sunlight. I'm writing this just inside a wall of insulating glass. The room is so bright I've had to draw the blinds a bit. Overhead, 100 tons of earth can no doubt feel the urgings of springtime in the roots. . . . Inside, the silence is so complete the loudest noise is the gliding of my pen across the paper. . . . I didn't plant the wild garden on the roof. The seeds arrived by breeze and bird and planted themselves in gratitude for my having added, not subtracted, land area when I built. . . . I'm underground, just where we all should be. Here, much of the rain that falls on the roof stays up there for days, percolating down through the deep humus and soil layers until it reaches the waterproofing, at which point it seeps out to the edge of the roof and drips into the surrounding soil. . . . Before the building was built the site was all barren subsoil, lifeless. Now it's a junior forest growing healthier by the year."

Looking Ahead from Below

"The resistance to underground architecture is due not only to inertia and unfamiliarity with earth-type building techniques but to fear of ridicule and fear of failure as well."

"Underground architecture is bound to succeed eventually. It has the most powerful of all possible allies: the living world. Rather than standing above Mother Earth, underground architecture lies in her arms."

Sources:

MalcolmWells.com

An Architect's Sketchbook of Underground Buildings, 1990.

Earth Sheltered Homes by Ahrens, Ellison, & Sterling, 1981.

"Nowhere to Go But Down," Progressive Architecture, 1965.

Recovering America: A More Gentle Way to Build, 1999.

"Underground! A More Gentle Way to Build," Designer/Builder, April 2000.

Underground Designs, 1977.

"In the early 1970s, realizing it was time to put up or shut up, I decided to build an [underground] architectural office for myself.... That's when the surprises began. The first one was that the open courtyard was actually quiet in spite of the truck traffic only 20 feet away. Another was the absolute silence of the innermost rooms."

"To cover the roof, rather than bring in topsoil from another site, I decided to see if topsoil could, in effect, be created. Once the brick and concrete structure had been waterproofed ... it was backfilled and covered with the lifeless subsoil we'd stockpiled when the site was excavated. Then, from a nearby town dump, we brought tons of leaves collected from the streets of that town and spread them there. The next spring, a miracle occurred: The site burst into life with every imaginable kind of weed and wildflower. It was an instant green area-without poisons, fertilizers, or topsoil. Within just a few years, I had a jungle on my hands.... At times, the birdsong seemed louder than the truck traffic. Maybe it was the site's way of expressing gratitude for having been spared the fate of every other site in the area; other sites, if they weren't asphalted to death, were kept in a perpetual stupor with poisons and mowing."

[In the photo at the top of this page, one corner of the roof of Wells' office building is barely visible through the empty trellis (at the back of the second rectangle from the bottom).]

Underground America Day

Wells' creativity and sense of humor are as fully developed as his understanding of earth-covered building design. His efforts to popularize underground architecture are often innovative. Every year he celebrates Underground America Day.

"On May 14th each year hundreds of millions of people all across this great land will do absolutely nothing about the national holiday I declared in 1974, and that's the way it should be. It's a holiday free of holiday obligations.... But if you're the partying type, here are some of the ways in which you can observe the big day: Dig a hole and put your house in it. Cover it up.... Touch a basement wall.... Draw a set of plans for an above-ground building-but don't build it."

Solaria

In the mid-1970s, near Philadelphia, Wells built the first version of one of his most famous residential designs. The long, narrow house's 16-foot-high south-facing wall consisted of solar collector panels above a wall of windows. The roof was covered with 2 feet of soil. The north wall was mostly buried, except for a short strip below the roof where windows alternated with massive support beams.

"All through the winter . . . we waited for word from the [house's owners]. January. February. March. . . . Finally Bob visited us and we all said, 'Well?' 'We didn't use the auxiliary heat at all.' So we had our first real proof, that under record conditions, solar heat and earth cover is a powerful combination, even in the northeastern part of the United States."

"This house is based on a design theme so simple, we've done dozens of variations on it and dozens more are possible."

Cape Cod House/Office (1980)

For passive solar-heating benefits, many earth-sheltered houses are designed with large window walls along an exposed south-facing wall. In 1980, Wells showed this concern does not have to be a constraint.

"When you have a stunning pond and forest view to the east you build facing east and find some other way to admit solar radiation."

The 110-foot-long house and office structure he built on Cape Cod was topped with a triple-glazed glass skylight that could be shielded with canvas shades to limit summer heat.

Underground Art Gallery

"The Underground Art Gallery on Cape Cod in which I have my office, built in 1988, is now almost totally hidden in the summertime by the lush growth on and around it. But when the leaves fall, its sixty-foot-long wall of glass admits warming sunlight. I'm writing this just inside a wall of insulating glass. The room is so bright I've had to draw the blinds a bit. Overhead, 100 tons of earth can no doubt feel the urgings of springtime in the roots. . . . Inside, the silence is so complete the loudest noise is the gliding of my pen across the paper. . . . I didn't plant the wild garden on the roof. The seeds arrived by breeze and bird and planted themselves in gratitude for my having added, not subtracted, land area when I built. . . . I'm underground, just where we all should be. Here, much of the rain that falls on the roof stays up there for days, percolating down through the deep humus and soil layers until it reaches the waterproofing, at which point it seeps out to the edge of the roof and drips into the surrounding soil. . . . Before the building was built the site was all barren subsoil, lifeless. Now it's a junior forest growing healthier by the year."

Looking Ahead from Below

"The resistance to underground architecture is due not only to inertia and unfamiliarity with earth-type building techniques but to fear of ridicule and fear of failure as well."

"Underground architecture is bound to succeed eventually. It has the most powerful of all possible allies: the living world. Rather than standing above Mother Earth, underground architecture lies in her arms."

Sources:

MalcolmWells.com

An Architect's Sketchbook of Underground Buildings, 1990.

Earth Sheltered Homes by Ahrens, Ellison, & Sterling, 1981.

"Nowhere to Go But Down," Progressive Architecture, 1965.

Recovering America: A More Gentle Way to Build, 1999.

"Underground! A More Gentle Way to Build," Designer/Builder, April 2000.

Underground Designs, 1977.

Unless otherwise attributed, all SubsurfaceBuildings.com content is © Loretta Hall, 2000-2024.

Malcolm Wells passed away November 27, 2009. His contributions to ecologically sensitive architecture will endure.

Unless otherwise attributed, all content is © Loretta Hall, 2000-2024.