Home

Hunkering Down for Defense

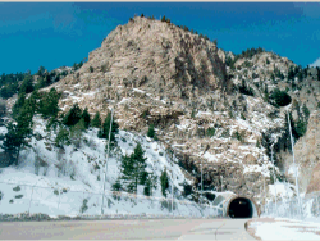

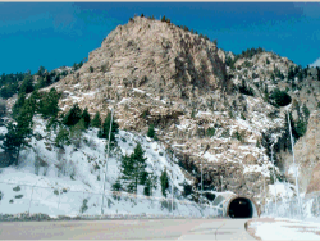

On September 11, 2001, Taliban and al-Qaeda troops hunkered down in a labyrinth of caverns and tunnels inside the mountains of Afghanistan. Half a world away, as the first hijacked airliner smashed into the World Trade Center, US Air Force fighter planes scrambled on orders issued from a command center deep within Cheyenne Mountain in Colorado. Have we really come very far since our prehistoric ancestors camped in caves to escape animals and enemies? A look at the history of underground defense installations says we have.

Early Man-Made Examples

Two millennia ago, early Christians hid from their pagan oppressors in the catacombs outside Rome. These structures were built as cemeteries, but they served well as places of refuge and occasionally for clandestine religious ceremonies. Hand-dug in porous rock, the passageways and chambers ultimately reached as far as four stories deep (up to 65 feet) and extended throughout an area of 600 acres. Ceilings were high (10-13 feet), but the hallways and rooms could hardly be described as spacious. Passages were only 3 feet wide, and chambers were typically about 12 feet square. By the fourth century, increasing size and usage of the catacombs prompted its builders to dig chimney-like shafts through the 20-foot layer of soil and rock that capped the structure. These shafts admitted both fresh air and light to the subterranean complex.

More in the realm of military defense, in 1502 Leonardo da Vinci designed a recessed building in which fortress guards could stand and shoot at eye level just above the surface. Actually more submerged than subterranean, the guardhouse was to be built in the middle of a moat, with the water level coming nearly up to its roof. Access from the chamber to the castle courtyard was through a tunnel that crossed under that moat, beneath a defensive wall, below a second moat concentric with the outer one, and underneath the fortress wall itself.

The Maginot Line

The Maginot Line was a more modern, underground defensive structure that gained notoriety for a deficiency unrelated to its basic design. Inspired by the trenches used so effectively by World War I soldiers, the idea was to construct a subterranean system to protect France from another German incursion. Construction began in 1929, and by 1940 there were 150 miles of tunnel-linked underground buildings in which troops could live and travel as well as fight. Some of the fortresses extended seven stories underground, and sections of tunnels were buried 100 feet below the surface. In a design reminiscent of da Vinci's, a series of gun turrets that punctuated the line allowed soldiers to fire inches above ground level; when not in use the steel turrets could be lowered, leaving only windowless, shallow dome sections visible.

The German army was able to advance past the Maginot Line in 1940, not by going through it, but by going around it. The line ended at the Ardennes, a forest so dense that the French could not envision tanks penetrating it. The Germans, however, managed to push through the forest and outflank the fortified line. Although only one of the Maginot Line's fortresses fell to military assault, France signed an armistice with Germany and turned over access to the underground system. During World War II, the German army used parts of it for storage and testing of ammunition and explosives, for factories, and, finally, for defense against the Allies.

World War II

Many other underground facilities played substantial roles in both the Atlantic and Pacific regions during World War II. The caves and tunnels on the Philippine island of Corregidor, for example, enabled 10,000 American and Filipino soldiers to resist intense Japanese assaults for a full month before a lack of supplies forced them to surrender in 1942. Just as General Douglas MacArthur had selected an underground installation on Corregidor as his final headquarters in the Philippines, war leaders on both sides of the European conflict operated from subterranean command posts. Adolph Hitler, of course, committed suicide in his "Fuhrerbunker" on the grounds of the Third Reich's Chancellery. Winston Churchill directed the defense of England from an underground complex dubbed the "Cabinet War Rooms." General Dwight Eisenhower commanded Allied forces throughout Western Europe from a 130-foot-deep bunker under the London subway.

The Cold War

Considering that experience, it is not surprising that later, as the Cold War got under way, President Eisenhower would look to the underground for secure emergency shelters to harbor key officials from the three branches of the American government. President Harry Truman laid the procedural groundwork in 1951 by creating the Civil Defense Administration (CDA), two years after the Soviet Union detonated its first nuclear bomb. An underground command post for the nation's military, begun during Truman's tenure, opened at Raven Rock Mountain, Pennsylvania, shortly after Eisenhower's 1953 inauguration.

President Eisenhower quickly began to address the issue of survival of the country's representative democracy through a strategy that came to be called "continuity of government" (COG). The idea was to respond to a national emergency by whisking government leaders to secret, protected federal relocation centers (FRCs) where they could keep the civilian government operating and direct a military defense action. By 1954, construction was under way on an underground refuge for the executive and judicial branches at Mount Weather, Virginia. A secret underground shelter for the legislative branch was completed in West Virginia in 1962.

During the 1950s and '60s, the US government applied Yankee ingenuity to the new kinds of threats inherent in the Cold War:

From the late 1970s and through the 1980s, Presidents Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan continued to rely on underground facilities to preserve and protect the United States against its Cold War enemies. Keeping the location of COG facilities secret offered a strategic protection to supplement the physical protection provided by their encasement in rock and soil. Because of the large amount of activity involved in their construction and the support services required for keeping them ready for immediate use, secrecy was enormously difficult to maintain. Consequently, in 1983, Reagan revised the strategy to increase the number of bunkers in order to keep enemies guessing where key personnel might be hiding. Ultimately, underground COG facilities numbered between 50 and 100.

Post-Cold War

Even after the Soviet Union dissolved in 1991, American defense leaders continued to devise subterranean countermeasures for threats from other nations and ideological groups. In this new era of more diverse enemies and weapons, shelters must be able to withstand not only bombs and nuclear fallout, but also chemical, biological, and electronic attacks. In 1998, at the request of the Department of Defense, the National Research Council conducted a workshop on the use of underground facilities (UGFs) for the protection of the nation's critical infrastructures. Critical infrastructures were defined as "systems whose incapacity or destruction would have a debilitating impact on the defense or economic security of the nation. They include telecommunications, electrical power systems, gas and oil, banking and finance, transportation, water supply systems, government services, and emergency services."

In light of their advantages and despite their limitations, underground facilities for infrastructure protection were generally viewed by workshop participants as worthy of further consideration and study. After the conference ended, the National Research Council issues a report titled Use of Underground Facilities to Protect Critical Infrastructures. Rather than specific recommendations, the document presented a summary of views espoused by the individual speakers, including the following passages:

"Going underground has some clear benefits, such as improved security and opportunities for dual uses [by the business sector as well as the government] of existing facilities."

"In the United States ... the initial construction cost of UGFs is considerably higher than the cost of above-ground facilities.... Over the entire life cycle of UGFs, there are operations and maintenance cost savings; in the long run, UGFs can be considered very cost competitive."

"Specific threats must be addressed, and UGFs must be well designed and difficult to attack. Technical concerns include external lifeline connections, fire, and protecting the facilities against chemical and biological weapons."

"Public perception is clearly a key issue. Corporate America needs to be made aware of the benefits of UGFs, and the public needs to be educated about their uses and benefits for protecting critical infrastructures."

Not to mention for protecting people. In immediate response to the terrorist attacks on September 11, ten Congressional leaders where whisked by helicopter to the COG facility inside Mount Weather. Vice President Dick Cheney slipped into a secure bunker underneath the White House. In an underground command post in Nebraska, President George W. Bush conducted a video conference with his advisors before returning to the nation's capitol and meeting with members of the national security team in a hardened chamber three floors beneath the East Wing of the White House.

Two millennia ago, early Christians hid from their pagan oppressors in the catacombs outside Rome. These structures were built as cemeteries, but they served well as places of refuge and occasionally for clandestine religious ceremonies. Hand-dug in porous rock, the passageways and chambers ultimately reached as far as four stories deep (up to 65 feet) and extended throughout an area of 600 acres. Ceilings were high (10-13 feet), but the hallways and rooms could hardly be described as spacious. Passages were only 3 feet wide, and chambers were typically about 12 feet square. By the fourth century, increasing size and usage of the catacombs prompted its builders to dig chimney-like shafts through the 20-foot layer of soil and rock that capped the structure. These shafts admitted both fresh air and light to the subterranean complex.

More in the realm of military defense, in 1502 Leonardo da Vinci designed a recessed building in which fortress guards could stand and shoot at eye level just above the surface. Actually more submerged than subterranean, the guardhouse was to be built in the middle of a moat, with the water level coming nearly up to its roof. Access from the chamber to the castle courtyard was through a tunnel that crossed under that moat, beneath a defensive wall, below a second moat concentric with the outer one, and underneath the fortress wall itself.

The Maginot Line

The Maginot Line was a more modern, underground defensive structure that gained notoriety for a deficiency unrelated to its basic design. Inspired by the trenches used so effectively by World War I soldiers, the idea was to construct a subterranean system to protect France from another German incursion. Construction began in 1929, and by 1940 there were 150 miles of tunnel-linked underground buildings in which troops could live and travel as well as fight. Some of the fortresses extended seven stories underground, and sections of tunnels were buried 100 feet below the surface. In a design reminiscent of da Vinci's, a series of gun turrets that punctuated the line allowed soldiers to fire inches above ground level; when not in use the steel turrets could be lowered, leaving only windowless, shallow dome sections visible.

The German army was able to advance past the Maginot Line in 1940, not by going through it, but by going around it. The line ended at the Ardennes, a forest so dense that the French could not envision tanks penetrating it. The Germans, however, managed to push through the forest and outflank the fortified line. Although only one of the Maginot Line's fortresses fell to military assault, France signed an armistice with Germany and turned over access to the underground system. During World War II, the German army used parts of it for storage and testing of ammunition and explosives, for factories, and, finally, for defense against the Allies.

World War II

Many other underground facilities played substantial roles in both the Atlantic and Pacific regions during World War II. The caves and tunnels on the Philippine island of Corregidor, for example, enabled 10,000 American and Filipino soldiers to resist intense Japanese assaults for a full month before a lack of supplies forced them to surrender in 1942. Just as General Douglas MacArthur had selected an underground installation on Corregidor as his final headquarters in the Philippines, war leaders on both sides of the European conflict operated from subterranean command posts. Adolph Hitler, of course, committed suicide in his "Fuhrerbunker" on the grounds of the Third Reich's Chancellery. Winston Churchill directed the defense of England from an underground complex dubbed the "Cabinet War Rooms." General Dwight Eisenhower commanded Allied forces throughout Western Europe from a 130-foot-deep bunker under the London subway.

The Cold War

Considering that experience, it is not surprising that later, as the Cold War got under way, President Eisenhower would look to the underground for secure emergency shelters to harbor key officials from the three branches of the American government. President Harry Truman laid the procedural groundwork in 1951 by creating the Civil Defense Administration (CDA), two years after the Soviet Union detonated its first nuclear bomb. An underground command post for the nation's military, begun during Truman's tenure, opened at Raven Rock Mountain, Pennsylvania, shortly after Eisenhower's 1953 inauguration.

President Eisenhower quickly began to address the issue of survival of the country's representative democracy through a strategy that came to be called "continuity of government" (COG). The idea was to respond to a national emergency by whisking government leaders to secret, protected federal relocation centers (FRCs) where they could keep the civilian government operating and direct a military defense action. By 1954, construction was under way on an underground refuge for the executive and judicial branches at Mount Weather, Virginia. A secret underground shelter for the legislative branch was completed in West Virginia in 1962.

During the 1950s and '60s, the US government applied Yankee ingenuity to the new kinds of threats inherent in the Cold War:

- A mountain was hollowed out to create a blast-proof vault to store enormous stacks of currency that would keep the American economy functioning after a devastating attack.

- Public buildings and basements whose walls and window structures were capable of blocking out sufficient levels of airborne radioactive particles were labeled with distinctive plaques. Citizens were urged to make note of the locations of these nuclear "fallout shelters." The city of St. Louis, Missouri, for example, identified and equipped 530 such havens, capable of sheltering more than 330,000 people.

- Throughout the nation, public service announcements and pamphlets urged citizens to build household bunkers in their back yards and stock them with water and nonperishable food. More than half a million families responded, building anything from a cramped, barren, 8-foot-by-10-foot concrete box to a comfortable two-story subterranean dwelling with its own power supply and sewage disposal system. In 1961, a newspaper in the heartland community of Amarillo, Texas, reported that construction of private fallout shelters was beginning at the rate of one a day.

From the late 1970s and through the 1980s, Presidents Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan continued to rely on underground facilities to preserve and protect the United States against its Cold War enemies. Keeping the location of COG facilities secret offered a strategic protection to supplement the physical protection provided by their encasement in rock and soil. Because of the large amount of activity involved in their construction and the support services required for keeping them ready for immediate use, secrecy was enormously difficult to maintain. Consequently, in 1983, Reagan revised the strategy to increase the number of bunkers in order to keep enemies guessing where key personnel might be hiding. Ultimately, underground COG facilities numbered between 50 and 100.

Post-Cold War

Even after the Soviet Union dissolved in 1991, American defense leaders continued to devise subterranean countermeasures for threats from other nations and ideological groups. In this new era of more diverse enemies and weapons, shelters must be able to withstand not only bombs and nuclear fallout, but also chemical, biological, and electronic attacks. In 1998, at the request of the Department of Defense, the National Research Council conducted a workshop on the use of underground facilities (UGFs) for the protection of the nation's critical infrastructures. Critical infrastructures were defined as "systems whose incapacity or destruction would have a debilitating impact on the defense or economic security of the nation. They include telecommunications, electrical power systems, gas and oil, banking and finance, transportation, water supply systems, government services, and emergency services."

In light of their advantages and despite their limitations, underground facilities for infrastructure protection were generally viewed by workshop participants as worthy of further consideration and study. After the conference ended, the National Research Council issues a report titled Use of Underground Facilities to Protect Critical Infrastructures. Rather than specific recommendations, the document presented a summary of views espoused by the individual speakers, including the following passages:

"Going underground has some clear benefits, such as improved security and opportunities for dual uses [by the business sector as well as the government] of existing facilities."

"In the United States ... the initial construction cost of UGFs is considerably higher than the cost of above-ground facilities.... Over the entire life cycle of UGFs, there are operations and maintenance cost savings; in the long run, UGFs can be considered very cost competitive."

"Specific threats must be addressed, and UGFs must be well designed and difficult to attack. Technical concerns include external lifeline connections, fire, and protecting the facilities against chemical and biological weapons."

"Public perception is clearly a key issue. Corporate America needs to be made aware of the benefits of UGFs, and the public needs to be educated about their uses and benefits for protecting critical infrastructures."

Not to mention for protecting people. In immediate response to the terrorist attacks on September 11, ten Congressional leaders where whisked by helicopter to the COG facility inside Mount Weather. Vice President Dick Cheney slipped into a secure bunker underneath the White House. In an underground command post in Nebraska, President George W. Bush conducted a video conference with his advisors before returning to the nation's capitol and meeting with members of the national security team in a hardened chamber three floors beneath the East Wing of the White House.

Photo courtesy of North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD).

On September 11, 2001, Taliban and al-Qaeda troops hunkered down in a labyrinth of caverns and tunnels inside the mountains of Afghanistan. Half a world away, as the first hijacked airliner smashed into the World Trade Center, US Air Force fighter planes scrambled on orders issued from a command center deep within Cheyenne Mountain in Colorado. Have we really come very far since our prehistoric ancestors camped in caves to escape animals and enemies? A look at the history of underground defense installations says we have.

Early Man-Made Examples

Two millennia ago, early Christians hid from their pagan oppressors in the catacombs outside Rome. These structures were built as cemeteries, but they served well as places of refuge and occasionally for clandestine religious ceremonies. Hand-dug in porous rock, the passageways and chambers ultimately reached as far as four stories deep (up to 65 feet) and extended throughout an area of 600 acres. Ceilings were high (10-13 feet), but the hallways and rooms could hardly be described as spacious. Passages were only 3 feet wide, and chambers were typically about 12 feet square. By the fourth century, increasing size and usage of the catacombs prompted its builders to dig chimney-like shafts through the 20-foot layer of soil and rock that capped the structure. These shafts admitted both fresh air and light to the subterranean complex.

More in the realm of military defense, in 1502 Leonardo da Vinci designed a recessed building in which fortress guards could stand and shoot at eye level just above the surface. Actually more submerged than subterranean, the guardhouse was to be built in the middle of a moat, with the water level coming nearly up to its roof. Access from the chamber to the castle courtyard was through a tunnel that crossed under that moat, beneath a defensive wall, below a second moat concentric with the outer one, and underneath the fortress wall itself.

The Maginot Line

The Maginot Line was a more modern, underground defensive structure that gained notoriety for a deficiency unrelated to its basic design. Inspired by the trenches used so effectively by World War I soldiers, the idea was to construct a subterranean system to protect France from another German incursion. Construction began in 1929, and by 1940 there were 150 miles of tunnel-linked underground buildings in which troops could live and travel as well as fight. Some of the fortresses extended seven stories underground, and sections of tunnels were buried 100 feet below the surface. In a design reminiscent of da Vinci's, a series of gun turrets that punctuated the line allowed soldiers to fire inches above ground level; when not in use the steel turrets could be lowered, leaving only windowless, shallow dome sections visible.

The German army was able to advance past the Maginot Line in 1940, not by going through it, but by going around it. The line ended at the Ardennes, a forest so dense that the French could not envision tanks penetrating it. The Germans, however, managed to push through the forest and outflank the fortified line. Although only one of the Maginot Line's fortresses fell to military assault, France signed an armistice with Germany and turned over access to the underground system. During World War II, the German army used parts of it for storage and testing of ammunition and explosives, for factories, and, finally, for defense against the Allies.

World War II

Many other underground facilities played substantial roles in both the Atlantic and Pacific regions during World War II. The caves and tunnels on the Philippine island of Corregidor, for example, enabled 10,000 American and Filipino soldiers to resist intense Japanese assaults for a full month before a lack of supplies forced them to surrender in 1942. Just as General Douglas MacArthur had selected an underground installation on Corregidor as his final headquarters in the Philippines, war leaders on both sides of the European conflict operated from subterranean command posts. Adolph Hitler, of course, committed suicide in his "Fuhrerbunker" on the grounds of the Third Reich's Chancellery. Winston Churchill directed the defense of England from an underground complex dubbed the "Cabinet War Rooms." General Dwight Eisenhower commanded Allied forces throughout Western Europe from a 130-foot-deep bunker under the London subway.

The Cold War

Considering that experience, it is not surprising that later, as the Cold War got under way, President Eisenhower would look to the underground for secure emergency shelters to harbor key officials from the three branches of the American government. President Harry Truman laid the procedural groundwork in 1951 by creating the Civil Defense Administration (CDA), two years after the Soviet Union detonated its first nuclear bomb. An underground command post for the nation's military, begun during Truman's tenure, opened at Raven Rock Mountain, Pennsylvania, shortly after Eisenhower's 1953 inauguration.

President Eisenhower quickly began to address the issue of survival of the country's representative democracy through a strategy that came to be called "continuity of government" (COG). The idea was to respond to a national emergency by whisking government leaders to secret, protected federal relocation centers (FRCs) where they could keep the civilian government operating and direct a military defense action. By 1954, construction was under way on an underground refuge for the executive and judicial branches at Mount Weather, Virginia. A secret underground shelter for the legislative branch was completed in West Virginia in 1962.

During the 1950s and '60s, the US government applied Yankee ingenuity to the new kinds of threats inherent in the Cold War:

A mountain was hollowed out to create a blast-proof vault to store enormous stacks of currency that would keep the American economy functioning after a devastating attack.

Public buildings and basements whose walls and window structures were capable of blocking out sufficient levels of airborne radioactive particles were labeled with distinctive plaques. Citizens were urged to make note of the locations of these nuclear "fallout shelters." The city of St. Louis, Missouri, for example, identified and equipped 530 such havens, capable of sheltering more than 330,000 people.

Throughout the nation, public service announcements and pamphlets urged citizens to build household bunkers in their back yards and stock them with water and nonperishable food. More than half a million families responded, building anything from a cramped, barren, 8-foot-by-10-foot concrete box to a comfortable two-story subterranean dwelling with its own power supply and sewage disposal system. In 1961, a newspaper in the heartland community of Amarillo, Texas, reported that construction of private fallout shelters was beginning at the rate of one a day.

As improved nuclear weapons escalated the threat of destruction, more elaborate ideas were framed for protecting key elements of the American way of life. During the 1960s, Presidents John Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson gave serious consideration to a Department of Defense recommendation to build a Deep Underground Command Center. This structure would burrow 3,500 feet -- two-thirds of a mile -- below the surface in the Washington, DC, area. The President and other key civilian and military leaders would be able to seek refuge there within 15 minutes. The Secretary of Defense predicted that such a structure would "withstand multiple direct hits of 200 to 300 MT [megaton] weapons bursting at the surface or 100 MT weapons penetrating to depths of 70-100 feet." Depending on its ultimate size, the cost of the facility was estimated to be between $110 million and $310 million.

From the late 1970s and through the 1980s, Presidents Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan continued to rely on underground facilities to preserve and protect the United States against its Cold War enemies. Keeping the location of COG facilities secret offered a strategic protection to supplement the physical protection provided by their encasement in rock and soil. Because of the large amount of activity involved in their construction and the support services required for keeping them ready for immediate use, secrecy was enormously difficult to maintain. Consequently, in 1983, Reagan revised the strategy to increase the number of bunkers in order to keep enemies guessing where key personnel might be hiding. Ultimately, underground COG facilities numbered between 50 and 100.

Post-Cold War

Even after the Soviet Union dissolved in 1991, American defense leaders continued to devise subterranean countermeasures for threats from other nations and ideological groups. In this new era of more diverse enemies and weapons, shelters must be able to withstand not only bombs and nuclear fallout, but also chemical, biological, and electronic attacks. In 1998, at the request of the Department of Defense, the National Research Council conducted a workshop on the use of underground facilities (UGFs) for the protection of the nation's critical infrastructures. Critical infrastructures were defined as "systems whose incapacity or destruction would have a debilitating impact on the defense or economic security of the nation. They include telecommunications, electrical power systems, gas and oil, banking and finance, transportation, water supply systems, government services, and emergency services."

In light of their advantages and despite their limitations, underground facilities for infrastructure protection were generally viewed by workshop participants as worthy of further consideration and study. After the conference ended, the National Research Council issues a report titled Use of Underground Facilities to Protect Critical Infrastructures. Rather than specific recommendations, the document presented a summary of views espoused by the individual speakers, including the following passages:

"Going underground has some clear benefits, such as improved security and opportunities for dual uses [by the business sector as well as the government] of existing facilities."

"In the United States ... the initial construction cost of UGFs is considerably higher than the cost of above-ground facilities.... Over the entire life cycle of UGFs, there are operations and maintenance cost savings; in the long run, UGFs can be considered very cost competitive."

"Specific threats must be addressed, and UGFs must be well designed and difficult to attack. Technical concerns include external lifeline connections, fire, and protecting the facilities against chemical and biological weapons."

"Public perception is clearly a key issue. Corporate America needs to be made aware of the benefits of UGFs, and the public needs to be educated about their uses and benefits for protecting critical infrastructures."

Not to mention for protecting people. In immediate response to the terrorist attacks on September 11, ten Congressional leaders where whisked by helicopter to the COG facility inside Mount Weather. Vice President Dick Cheney slipped into a secure bunker underneath the White House. In an underground command post in Nebraska, President George W. Bush conducted a video conference with his advisors before returning to the nation's capitol and meeting with members of the national security team in a hardened chamber three floors beneath the East Wing of the White House.

Two millennia ago, early Christians hid from their pagan oppressors in the catacombs outside Rome. These structures were built as cemeteries, but they served well as places of refuge and occasionally for clandestine religious ceremonies. Hand-dug in porous rock, the passageways and chambers ultimately reached as far as four stories deep (up to 65 feet) and extended throughout an area of 600 acres. Ceilings were high (10-13 feet), but the hallways and rooms could hardly be described as spacious. Passages were only 3 feet wide, and chambers were typically about 12 feet square. By the fourth century, increasing size and usage of the catacombs prompted its builders to dig chimney-like shafts through the 20-foot layer of soil and rock that capped the structure. These shafts admitted both fresh air and light to the subterranean complex.

More in the realm of military defense, in 1502 Leonardo da Vinci designed a recessed building in which fortress guards could stand and shoot at eye level just above the surface. Actually more submerged than subterranean, the guardhouse was to be built in the middle of a moat, with the water level coming nearly up to its roof. Access from the chamber to the castle courtyard was through a tunnel that crossed under that moat, beneath a defensive wall, below a second moat concentric with the outer one, and underneath the fortress wall itself.

The Maginot Line

The Maginot Line was a more modern, underground defensive structure that gained notoriety for a deficiency unrelated to its basic design. Inspired by the trenches used so effectively by World War I soldiers, the idea was to construct a subterranean system to protect France from another German incursion. Construction began in 1929, and by 1940 there were 150 miles of tunnel-linked underground buildings in which troops could live and travel as well as fight. Some of the fortresses extended seven stories underground, and sections of tunnels were buried 100 feet below the surface. In a design reminiscent of da Vinci's, a series of gun turrets that punctuated the line allowed soldiers to fire inches above ground level; when not in use the steel turrets could be lowered, leaving only windowless, shallow dome sections visible.

The German army was able to advance past the Maginot Line in 1940, not by going through it, but by going around it. The line ended at the Ardennes, a forest so dense that the French could not envision tanks penetrating it. The Germans, however, managed to push through the forest and outflank the fortified line. Although only one of the Maginot Line's fortresses fell to military assault, France signed an armistice with Germany and turned over access to the underground system. During World War II, the German army used parts of it for storage and testing of ammunition and explosives, for factories, and, finally, for defense against the Allies.

World War II

Many other underground facilities played substantial roles in both the Atlantic and Pacific regions during World War II. The caves and tunnels on the Philippine island of Corregidor, for example, enabled 10,000 American and Filipino soldiers to resist intense Japanese assaults for a full month before a lack of supplies forced them to surrender in 1942. Just as General Douglas MacArthur had selected an underground installation on Corregidor as his final headquarters in the Philippines, war leaders on both sides of the European conflict operated from subterranean command posts. Adolph Hitler, of course, committed suicide in his "Fuhrerbunker" on the grounds of the Third Reich's Chancellery. Winston Churchill directed the defense of England from an underground complex dubbed the "Cabinet War Rooms." General Dwight Eisenhower commanded Allied forces throughout Western Europe from a 130-foot-deep bunker under the London subway.

The Cold War

Considering that experience, it is not surprising that later, as the Cold War got under way, President Eisenhower would look to the underground for secure emergency shelters to harbor key officials from the three branches of the American government. President Harry Truman laid the procedural groundwork in 1951 by creating the Civil Defense Administration (CDA), two years after the Soviet Union detonated its first nuclear bomb. An underground command post for the nation's military, begun during Truman's tenure, opened at Raven Rock Mountain, Pennsylvania, shortly after Eisenhower's 1953 inauguration.

President Eisenhower quickly began to address the issue of survival of the country's representative democracy through a strategy that came to be called "continuity of government" (COG). The idea was to respond to a national emergency by whisking government leaders to secret, protected federal relocation centers (FRCs) where they could keep the civilian government operating and direct a military defense action. By 1954, construction was under way on an underground refuge for the executive and judicial branches at Mount Weather, Virginia. A secret underground shelter for the legislative branch was completed in West Virginia in 1962.

During the 1950s and '60s, the US government applied Yankee ingenuity to the new kinds of threats inherent in the Cold War:

A mountain was hollowed out to create a blast-proof vault to store enormous stacks of currency that would keep the American economy functioning after a devastating attack.

Public buildings and basements whose walls and window structures were capable of blocking out sufficient levels of airborne radioactive particles were labeled with distinctive plaques. Citizens were urged to make note of the locations of these nuclear "fallout shelters." The city of St. Louis, Missouri, for example, identified and equipped 530 such havens, capable of sheltering more than 330,000 people.

Throughout the nation, public service announcements and pamphlets urged citizens to build household bunkers in their back yards and stock them with water and nonperishable food. More than half a million families responded, building anything from a cramped, barren, 8-foot-by-10-foot concrete box to a comfortable two-story subterranean dwelling with its own power supply and sewage disposal system. In 1961, a newspaper in the heartland community of Amarillo, Texas, reported that construction of private fallout shelters was beginning at the rate of one a day.

As improved nuclear weapons escalated the threat of destruction, more elaborate ideas were framed for protecting key elements of the American way of life. During the 1960s, Presidents John Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson gave serious consideration to a Department of Defense recommendation to build a Deep Underground Command Center. This structure would burrow 3,500 feet -- two-thirds of a mile -- below the surface in the Washington, DC, area. The President and other key civilian and military leaders would be able to seek refuge there within 15 minutes. The Secretary of Defense predicted that such a structure would "withstand multiple direct hits of 200 to 300 MT [megaton] weapons bursting at the surface or 100 MT weapons penetrating to depths of 70-100 feet." Depending on its ultimate size, the cost of the facility was estimated to be between $110 million and $310 million.

From the late 1970s and through the 1980s, Presidents Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan continued to rely on underground facilities to preserve and protect the United States against its Cold War enemies. Keeping the location of COG facilities secret offered a strategic protection to supplement the physical protection provided by their encasement in rock and soil. Because of the large amount of activity involved in their construction and the support services required for keeping them ready for immediate use, secrecy was enormously difficult to maintain. Consequently, in 1983, Reagan revised the strategy to increase the number of bunkers in order to keep enemies guessing where key personnel might be hiding. Ultimately, underground COG facilities numbered between 50 and 100.

Post-Cold War

Even after the Soviet Union dissolved in 1991, American defense leaders continued to devise subterranean countermeasures for threats from other nations and ideological groups. In this new era of more diverse enemies and weapons, shelters must be able to withstand not only bombs and nuclear fallout, but also chemical, biological, and electronic attacks. In 1998, at the request of the Department of Defense, the National Research Council conducted a workshop on the use of underground facilities (UGFs) for the protection of the nation's critical infrastructures. Critical infrastructures were defined as "systems whose incapacity or destruction would have a debilitating impact on the defense or economic security of the nation. They include telecommunications, electrical power systems, gas and oil, banking and finance, transportation, water supply systems, government services, and emergency services."

In light of their advantages and despite their limitations, underground facilities for infrastructure protection were generally viewed by workshop participants as worthy of further consideration and study. After the conference ended, the National Research Council issues a report titled Use of Underground Facilities to Protect Critical Infrastructures. Rather than specific recommendations, the document presented a summary of views espoused by the individual speakers, including the following passages:

"Going underground has some clear benefits, such as improved security and opportunities for dual uses [by the business sector as well as the government] of existing facilities."

"In the United States ... the initial construction cost of UGFs is considerably higher than the cost of above-ground facilities.... Over the entire life cycle of UGFs, there are operations and maintenance cost savings; in the long run, UGFs can be considered very cost competitive."

"Specific threats must be addressed, and UGFs must be well designed and difficult to attack. Technical concerns include external lifeline connections, fire, and protecting the facilities against chemical and biological weapons."

"Public perception is clearly a key issue. Corporate America needs to be made aware of the benefits of UGFs, and the public needs to be educated about their uses and benefits for protecting critical infrastructures."

Not to mention for protecting people. In immediate response to the terrorist attacks on September 11, ten Congressional leaders where whisked by helicopter to the COG facility inside Mount Weather. Vice President Dick Cheney slipped into a secure bunker underneath the White House. In an underground command post in Nebraska, President George W. Bush conducted a video conference with his advisors before returning to the nation's capitol and meeting with members of the national security team in a hardened chamber three floors beneath the East Wing of the White House.

Photo courtesy of North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD).

Unless otherwise attributed, all SubsurfaceBuildings.com content is © Loretta Hall, 2000-2024.

Unless otherwise attributed, all SubsurfaceBuildings.com content is © Loretta Hall, 2000-2024.

Unless otherwise attributed, all SubsurfaceBuildings.com content is © Loretta Hall, 2000-2024.